Dear Friends:

On Sunday March 30th at approximately 2:30 pm my climbing partner Steve Snopkowski and I were struck by an avalanche while climbing the North Gully in Huntington ravine on Mount Washington. The avalanche was triggered by a two climbers just reaching the rim 800 feet above. They reported a fracture 60 feet wide by four feet deep.

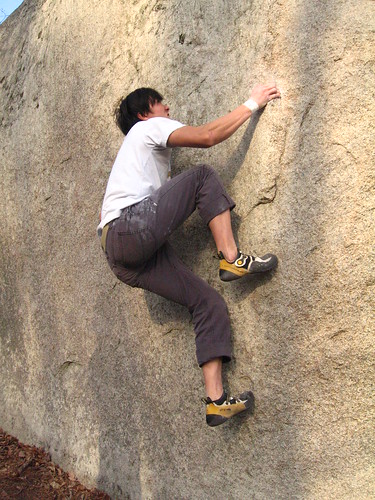

I led the first pitch which consisted of a 50 or so feet of stepped ice bulges followed by about 40 feet of snow climbing up a slope to a fixed two piton anchor just below another low angle ice flow. Upon arriving at the fixed anchor, I clipped one of my ropes to it with a quick draw, opting to remain on belay from below while I shed my pack and added more gear to the anchor before I committed to it.

Minutes later, as I was equalizing a cam into the anchor matrix I heard a rumbling sound similar to an overhead jet. I looked up to see snow pouring over the ice bulges above. I called out “avalanche!” quickly, made myself small below my hanging backpack, and grabbed hold of my ice tools in an effort to hold on.

Within a split second I was swept from my stance at the anchor. I tumbled in darkness several times down the snow slope, and over the lip of the ice bulge below. I was arrested by the rope in an upright position a few feet beyond the lip of the ice. I could see light as snow and ice flowed past me overhead. And then it stopped. I quickly checked myself for injury.

Steve was initially unanchored at the bottom of the pitch. He belayed from a snow shelf we had cut to the left of the ice. When I fell, he was sucked up into the ice and struck it. He then swung right towards the path of the slide.

“Holy f-ing sh!t Steve are you okay!?” I called to Steve to check his condition. He was okay, but assertively told me he needed to take me off belay and wanted to retreat immediately. I agreed. I clipped into a cam that I placed on the way up, hastily placed a screw, clipped into it also and called “off belay”. He lowered himself to the snow and quickly climbed up and left to a rock wall to build an anchor out of the way of potential slides to follow.

Some voices shouted from across the ravine asking if we needed help. We declined.

I prussiked up the rope, hauled my self over the ice bulge and marched up the snow and clipped into the anchor. My backpack was still there, but my ice tools were gone. Thinking back I don’t know why that surprised me.

We were using double 8 mm ropes, and my tie in knot was about the size of my thumb. It must have taken more than 5 minutes to untie that knot. At one point I had my knife out, but didn’t use it because I felt frantic, and was afraid that I would cut something I shouldn’t.

Steve and I communicated many times during this time, to ensure we were both still okay. At some point I heard snowmobiles whine their way up to the ravine floor and asked “Do you think that’s for us?” They were.

Finally I was free of the knot. By this time, there were two snowmobiles on the ravine floor, and a two figures hiking up to us. I tied the ropes together, set up my rappel rig, cleaned our gear, put on my pack and started down. I cleaned all my protection from the pitch, swung left to Steve’s anchor, and clipped both ropes in so he could reach them and rapped to rope ends on the snow below. I told Steve I was off rappel and walked a few feet climbers left to the toe of a rock buttress.

Steve jumped on rappel and met me a few moments later. We pulled the ropes, and he gave me one of his tools and a leash for my walk down. The snow slope directly below looked dangerous, so I traversed left over the rock buttress a few yards and climbed down circuitously toward the figures heading my way, avoiding any steep or questionable slopes. There was now a snow cat and a few more folks down there.

I met a ranger named Brian a few hundred feet below. He asked me if we were the only climbers involved. I told him someone spotted another party on the route earlier that day, but we never saw them and that the slide came from above. He asked if we called 911, I said we did not. (We later learned that a soloist on central gully called 911). He looked me over quickly and said we would talk some more on the ravine floor. I kept climbing down. He went up to check on Steve.

At the floor of the ravine, I stopped at the boulders by the snow machines to wait for Steve. I took off my crampons, poured myself some tea and inspected my self further for injury. Brian met me there shortly and returned one of my axes. He took my story a couple of times, and recorded my information. He looked me over for injury. We were joined by another ranger named Chris who returned my other missing tool. (Not only did God want me to live, he also wants me to continue to climb ice.) There was also a search dog playing in the snow.

Steve and I both cracked our helmets. The rope that did not arrest me was cut 1/3 way through about 30 feet from the end. My backpack was abraded on one side and its internal frame deformed. I lost my sunglasses, a v-threading tool, and initially both my ice tools.

I suffered a few abrasions and bumps on left side of my face, a contusion on my left forearm and pain in my right shoulder. (I may have damaged my rotator cuff) Steve had some mild pain in his lower back and neck.

We both passed the Forest Service’s field exam and were not required to go to the hospital. In an effort to be most self reliant we offered to hike down to the Harvard cabin, but the rangers insisted we ride in the snow cat. We returned to our igloo and hiked out the next morning.

There were forces that were working against us that we failed to recognize. The previous day, the avalanche danger for all routes in Huntington ravine was High. On this day, it was Low for all routes, except Damnation and North, which were reported as Moderate. It was a blue bird day, with high temps in the sun. Mostly all the routes had parties on them, some had multiple parties.

All the routes had parties on them and we assessed climbing below climbers would be ok if they were not directly above or in close proximity to us. Pinnacle Gully looked like a bowling alley with constant rain of falling ice. We never saw the climbers who were above us until they walked into the base of the ravine to check on us.

On our drive up Steve and I both agreed climbing under Moderate avalanche danger was an acceptable risk. I assumed that we would not trigger a slide, and therefore, others wouldn’t. We never put two and two together.

We went up there for the last licks. Climbing ice harbors a sense of immediacy or urgency not found in rock climbing. Routes that are in shape one day may not be in shape the next. Combined with the time limitations of our lives, the tendency to “go for it” is high.

I believe the drastic reduction of avalanche danger for Huntington ravine as a whole combined with the clear day and warm temperature lulled us into believing we were safe. Thinking back now, It was alarmingly easy to turn a blind eye toward the real dangers.

We narrowly escaped the grim reapers calling with not so much as a slap on the wrist. I can not take credit for the relatively low expense of this event. I wonder in amazement how the number of variables fell into place to minimize the price we paid. The questions of “what-if” keep replaying in my mind.

For some reason I didn’t tie into the top anchor upon reaching it, which I would normally do. I instead clipped it for protection and remained on belay from below while I added to it. Who knows if it would have held? Would it have been better to be secured to the anchor while subjected to the full deluge of debris, or was it better to be carried a distance until I was sheltered from the tonnage? If we were five minutes faster, that would have been the case. We would’ve been committed to the top anchor, and subjected to the full bore.

If I hadn’t reached the anchor, everything would have all hinged on the small cam I placed, and that wouldn’t have kept me out of the run out below.

If we were 20 minutes faster, Steve would be on the second pitch ice, or above. Our plan was to solo the easier snowfields above.

What if I was leashed or tethered to my ice tools? Ugly.

What if the fate of Rock Paper Scissors had not designated me to lead the first pitch?

Who knows?